A 2021 interactive feature in The Guardian. Many more graphs at the link above.

Spoiler Alert: This article, excerpts from the article linked above, concerns developments in the later acts of Love, Love, Love. If you’d like to experience the play with the swerves and surprises that Mike Bartlett wrote for you, then hold off on reading this until you’ve seen the production. Plot and culture spoilers follow.

Years of selling off social housing followed by more than two decades of a property market fuelled by cheap credit have put households who do not own homes in a difficult position. High rents make it hard to save enough for mortgages that would cost less each month. Runaway house prices mean that for some it is impossible to ever save a big enough deposit to raise a mortgage. Low interest rates make property attractive to investors and help those who can afford a deposit raise big sums to buy—but they are no help to those who are saving up.

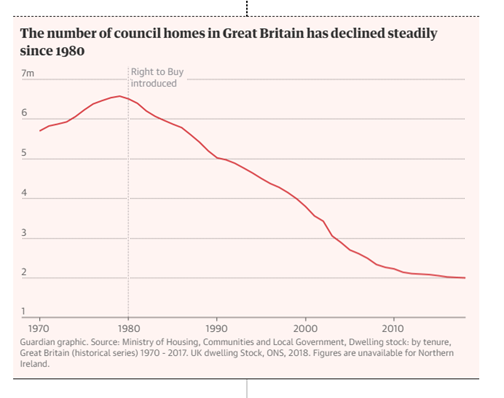

At the beginning of the 1970s almost a third of homes across Great Britain were affordable social housing provided by local authorities, according to government data. This provided a decent alternative to home ownership. For those who could buy, the average price in the UK was £4,057. By the next decade things were beginning to look different.

The right to buy is a good place to start unpicking the current housing crisis. The scheme, which enabled council tenants to buy their homes for a reduced price, had existed for years, but the Thatcher government turbo-charged it with big discounts introduced in the Housing Act of 1980. Over time, the sums of money councils could keep to create new homes was reduced, and the number of replacement properties fell.

Within five years, in England alone half a million council homes had been sold under the initiative. Between right to buy sales, demolitions and the later transfer of properties to housing associations, the availability of council housing has plummeted since the 1980s.

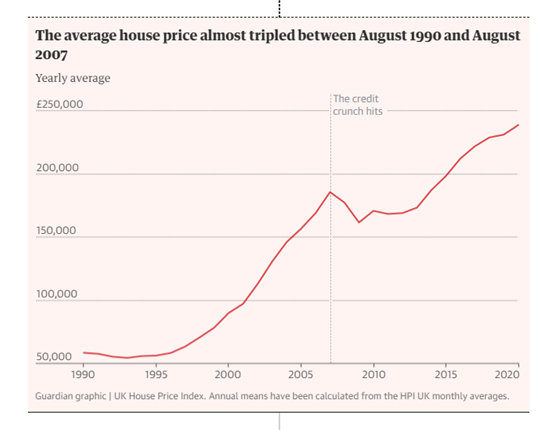

At the same time as council housing stock was diminishing, something else was afoot. The financial sector began a large-scale deregulation that continued throughout the 80s. Mortgages became more readily available and lenders could charge what they wanted. The days of having to prove you could save before you could borrow were over, and more money came into the system.

The 1988 Housing Act enabled housing associations to source private money to build new homes and repair existing ones. These independent not-for-profit organisations were originally funded by philanthropy, but in the 1970s were granted access to public funding to build homes. This new act gave them powers that councils did not have, so many transferred the ownership of homes to the associations. A quarter of a million houses had been transferred by 1997, and this practice continued under New Labour.

The act also introduced assured shorthold tenancies, which made owning a rental property more attractive to individual investors – another factor contributing to the rise in house prices.

House prices rose significantly from 1983 onwards, but crashed at the end of the decade as interest rates rose to almost 15% and the economy fell into recession. The subsequent fall in the early 1990s led many borrowers into negative equity – their mortgages were bigger than the value of the homes they were secured on.

Some borrowers handed back their keys to their lender, others fell behind on payments. Repossessions rose, peaking at 75,500 in 1991. These homes went back on the market, depressing prices further.

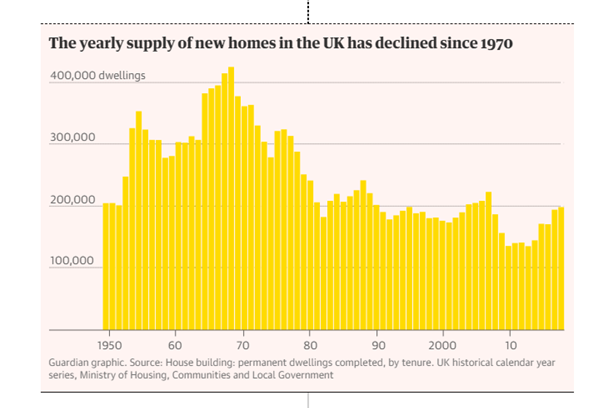

Fewer controls on mortgage lending meant more people could buy homes, but this was offset by the fact there were not enough homes being built. In 1992, the number of new homes completed in the UK was 179,100 – just over half the number built 20 years earlier. The growing demand drove up prices.

From the end of 1993 house prices began rising again. Within 10 years mortgage payments went up from about a fifth of the average pay packet of a first-time buyer to approximately a third, according to the Nationwide affordability index.

In September 1996 the Association of Residential Letting Agents (ARLA) and four lenders launched a “buy-to-let initiative”, making it easier for individuals to invest in property by offering specialist mortgages that take into account rental incomes. Over the next two decades falling interest rates and rising house prices persuaded more and more people that the property market was a good place to invest. In 2014, almost 200,000 buy-to-let mortgages were approved. Not only did this expand the rental market but it was another element driving house sale prices up.

Northern Rock launched its Together mortgage – a home loan that offered borrowers the chance to take on debt equal to 125% of the value of the property they were buying. The same year, the total number of new houses built by councils in England stood at a mere 50.

Among the other innovations in the housing market were self-certification mortgages – these were designed to help the self-employed and other borrowers with incomes from multiple sources to get mortgages without showing payslips. But as the housing market took off in the early 2000s they became more commonplace, along with “fast-track” loans where incomes were not verified. Regulators and politicians started to become concerned about this part of the market.

Interest-only mortgages also became more common, as borrowers who could not afford to pay off some of their home loan each month took the cheaper option – and a gamble that house prices would continue to rise and they would be able to pay off the loan eventually. After the banking crisis strict rules were put in place to curb these kinds of lending.

House prices soared in Britain … and then the US firm Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy, triggering a global financial crash. UK lenders took riskier mortgage products off the market and significantly cut their lending. As a result, it became more difficult to get a mortgage, particularly as the recession hit people’s jobs and savings. Against a backdrop of dwindling social housing provision and out-of-reach mortgages, more people were pushed into private renting. The percentage of owner-occupied properties began to fall.

As the impact of the credit crunch rippled across the country, repossessions were kept in check by historically low interest rates and rules forcing lenders to do their best to help people keep their homes.

As well as helping people stay in their homes, this cheap credit made property look a good investment to those with spare cash, and over the next few years fuelled some parts of the market.

The percentage of homes provided by councils fell from 32% in 1977 to a mere 9% in Great Britain. The figure continued to fall the following decade, hitting 7% in 2018. For those who qualified for a mortgage, interest rates had never been lower – the base rate was slashed to just 0.5% and the cost of home loans fell too.

The number of new houses completed in the UK dropped to 135,990, the lowest figure since 1946. In 2013 it fell even further to 135,590. The population, however, continued to grow, increasing housing demand.

The coalition government introduced a new form of tenure, called “affordable rent”. The hope was that making tenants pay up to 80% of the market rent – far above social housing rates – would enable more new houses to be built. These prices were far out of reach for many low-income earners in some parts of the country: Westminster council warned in 2013 that at 80% of market rates, households would have to earn £58,000 a year to afford a one-bedroom flat.